August 15, 2019

CANDON CITY, Ilocos Sur and Manila—The window of a northbound red bus along MacArthur Highway frames a blurry but picturesque swath of greenery still glistening from the early morning downpour.

Again July has arrived, time like a blur as four months prior the landscape was also painted brown mirroring this northern Philippine countryside’s pride produce: tobacco.

This day the landscape was also dotted by bobbing figures: farmers on rice paddies. They fight the sun with wide-brim buntal hats and the yellow and red long sleeves of camisa de chino. The towering Mount Tirad, the province’s third-highest mountain, lends a faint shadow.

The farmers have to wait until October before they can begin growing tobacco again. The waiting extends for 150 days when harvesting begins in March until April.

For now, they trust the rice seeds of the grass species Oryza sativa that they’re planting would tide them over. Some would say it’s a misplaced trust as the buying price of palay declined to a 2-year low of P17.85 per kilogram in end-June with the spike in rice imports following the liberalization of the rice trade.

Some concede that if only better opportunities exist out there, they would abandon these lands for good.

Their hopes to live a bare minimum life, therefore, rest upon tobacco. After all, this town is the country’s tobacco capital. But some would consider this as false hope as the number of tobacco farmers and the land area for tobacco growing have been contracting over the years.

In limbo

DUSK settled on July 25 and Reynaldo Acosta was slumped on a worn gray sofa. His eyes are glued to the live television broadcast of President Rodrigo Duterte leading an entourage on the newly inaugurated bypass road in Candon, 10 kilometers southeast of Acosta’s home in Santa Lucia.

The evening news came showing the President signing into law the imposition of higher taxes on tobacco products.

The 55-year-old Acosta never smoked his whole life but the news affected him more than it did a chain-smoker. Another round of sin-tax hikes, another year of lower income, he mumbled as newscasters switched to talking about an actress’s gym workout program.

Acosta has spent over half his life as a farmer supplying tobacco for the country’s biggest tobacco growing and processing company. With the impending implementation of heavier taxes on tobacco items, he is left with two options: to stay or leave town. The latter means abandoning tobacco planting.

Across Acosta’s is Andrea Reyes’s house where the 70-year-old also mulls the future.

It’s minutes before midnight but Reyes has just woken up having slept off exhaustion from working the whole day on her farm.

Her house in Banayoyo, a municipality 10 kilometers northeast of Candon, was visited by gloom after learning the news about a tobacco tax hike.

Like Acosta, Reyes ran the numbers in her head and sighed: her take-home income from tobacco farming next year will be reduced with higher taxes on smoking products in place.

Reyes has been growing tobacco since the company buying their harvest arrived in 1964.

“Up to now, I’m still here,” Andrea said, adding she’s proud of sticking with the tobacco-growing sector through eight presidents. “I tried shifting to other crops, but none can equal the income I’m getting from tobacco farming. It used to be the best source of income here in Ilocos Sur; but things have changed over the past years.”

New law

DUTERTE signed Republic Act (RA) 11346 on July 25, which would further increase the tax slapped on tobacco products starting January 1, 2020.

RA 11346, or the Tobacco Tax Law of 2019, increases the excise tax from the current P35 per pack to P45, or less than a dollar, per pack in 2020. This is followed by a series of P5 hikes until the rate reaches P60 ($1.15) in 2023. By 2024 and every year thereafter, the increase hits 5 percent.

RA 11346 did not only raise excise taxes but also put a cap on the share of tobacco-producing provinces from government revenues.

Provinces producing Virginia tobacco would still receive 15 percent of the tobacco excise tax the government collected. However, the share shouldn’t exceed P15 billion.

Provinces producing burley and native tobacco would now receive 5 percent instead of 15 percent of government revenues. Their share would be capped at P4 billion.

The Tobacco Tax Law also expanded the programs that local government units (LGUs) of tobacco-producing provinces could fund using their share of the revenues.

Under the law, the share in government revenues would be directly remitted to the tobacco-producing provinces.

Total recall

THE head of the National Federation of Tobacco Farmers Associations and Cooperatives (NFTFAC) said the increases in excise taxes would end in lower buying prices.

Bernard R. Vicente, NFTFAC’s president, explained that the reduction in consumption of cigarette would discourage manufacturers from producing more. This, he said, would reduce the volume of tobacco manufacturers buy from farmers.

“Dahil po doon hindi na po kami puwede magtanim ng magtanim at ang bilang po ng hektaryang tatamnaman namin ay mababawasan at ganoon din ang kita po namin every season [We can no longer plant tobacco at the pace we had prior to the signing of the law. Likewise, we have to cut the size of land we allot for farming. At the end of the day, it would negatively impact our income],” Vicente told the BusinessMirror.

Indeed, it is a case of supply and demand economics. When demand for cigarettes declines on higher taxes, manufacturers are compelled to adjust their production downward. As such, they buy less from farmers like Acosta and Reyes for their tobacco leaf requirement.

“We are hit hardest when the government increases taxes on tobacco. We cannot demand for higher buying prices of tobacco leaf because traders and firms will just say demand has gone down,” Reyes said in an interview with the BusinessMirror.

Earners’ woes

DEMAND is just one of manufacturers’ worries; supply is, too. And supply comes from the number of producers, which has been going down.

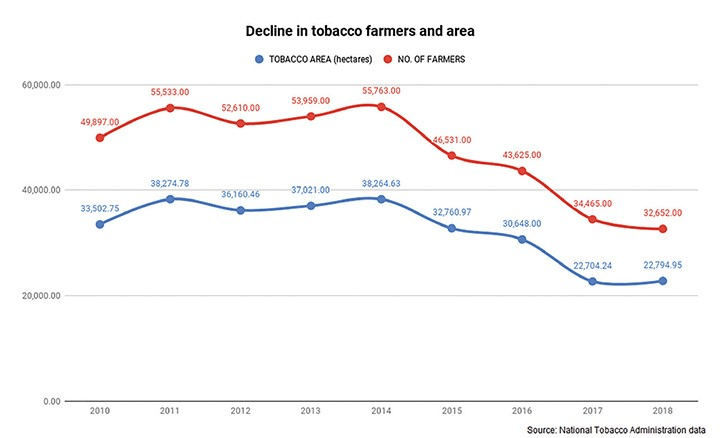

The number of farmers engaged in tobacco planting fell 5.28 percent to 32,652 in 2018, from 34,465 in 2017, records from the National Tobacco Administration (NTA) show.

At the start of the decade, there were some 49,897 tobacco planters in the Philippines. However, as tax hikes were rolled out on tobacco products, the headcount of farmers dropped 4.6 percent steadily every year from 2010 until 2018.

Acosta himself witnessed some of his friends leave the sector for good. He still wrestles with such a decision.

Because for one, he is managing three hectares of land where he cultivates tobacco during the dry season, and, second, how could he turn his back on a valuable memory?

“I was able to send my kids to school using income [from tobacco growing and] my siblings finished their studies with the money they earned from planting tobacco,” Acosta told the BusinessMirror. “We know the value of tobacco. We are used to growing it and I see myself and my family depending on it no matter what.”

For Reyes, she still has lots of mouth to feed and dreams to fulfill. She said she was able to support the education of her three children—one of whom graduated with a double degree—through income from tobacco farming.

The septuagenarian has no plans of calling it quits as she still wants to support her grandchildren.

Growers’ ills

Marcelino N. Biala, executive of the company that buys from farmers like Acosta and Reyes, believes the Tobacco Tax Law has thrown a monkey wrench in the gears of the tobacco industry.

Biala knows what he’s talking about: he’s been in the industry for 37 years—22 years for the private sector, 15 years for the government.

“As someone who has been in the heart of the industry for so long, I know the taxes will affect the behavior of our clients. Their purchases will certainly be lesser next year, when the tax hikes are applied,” Biala said. “Of course, the higher the consumer prices, the lower the demand. At the tail of the supply chain, the farmers are sure to suffer.”

Biala is the director for growing operations of a Richmond, Virginia-headquartered multinational firm.

As an executive of a contractor, Biala said it is but expected for tobacco manufacturers to buy less processed leaf from them next year with higher taxes in place.

“It is difficult to explain to farmers why we are buying their produce at lower prices and lesser volume,” he said.

Rising costs

FOR 67-year-old tobacco farmer Ernesto Lacaden Calindas, prices of their tobacco are just one of his worries.

Calindas, who has been planting tobacco for 20 years, has seen production costs ever rising, with the scarcity of farm workers as one of the reasons.

He said he’s now paying P350 (nearly $7) per hectare per head since laborers have been scarce. It used to be less than P300 (about $5.73 at current exchange rates). Laborers, he explained, have opted to shift to other sectors such as construction, which offers way higher wages. To note, the legislated minimum daily wage in Ilocos Sur for plantation workers is pegged at P295 (about $5.64) and P282 ($5.39) for non-plantation workers.

Another cost is the shortage in fuelwood, which farmers use in curing or cooking tobacco, Calindas said. He spends around P60,000 ($1,146.25) for his total fuelwood requirement at an estimated current cost of P1,000 ($19.10) per cubic meter.

Calindas estimates the production cost of tobacco right now is at least P130,000 ($2,483.55) per hectare. A farmer should produce at least 1,800 kilograms of tobacco to break even, he added.

Industry decline

DECLINING: this is how government data paints the country’s tobacco industry in terms of output, farmers and area in the past decade.

The industry attributed the decline in these three areas to farmers who are aging and who are migrating to higher-income-generating jobs, such as construction work. The industry also blames higher excise taxes.

“We used to produce 160 billion sticks of cigarettes but it went down to 74 billion sticks in 2017,” NTA chief Roberto L. Seares told the BusinessMirror.

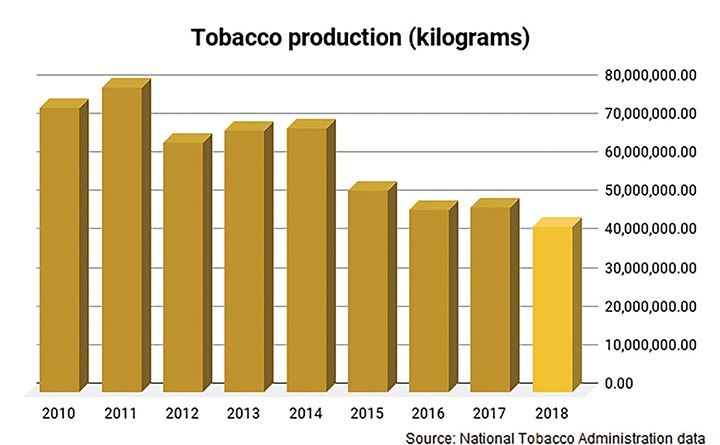

The country’s tobacco output declined at a compound annual growth rate of 5.76 percent from 2010 to 2018.

Tobacco production in 2018 fell to a decade-low of 43.241 million kilograms, which is 10.25 percent lower than the 48.179 million kilograms recorded in 2017.

Tobacco output peaked in 2011 at 79.329 million kilograms, just a year before the Sin Tax Law of 2012 was enacted.

Meanwhile, the area planted with tobacco has declined by an average of 4.19 percent from 2010 to 2018. Total tobacco area last year was estimated at 22,794.95 hectares, which is nearly 32 percent smaller than the 33,502.75 hectares recorded in 2010.

Top buyers

SEARES, however, said the NTA couldn’t “do anything about it [tobacco tax law].

“We just have to support it and help the government,” he said recalling the months-long deliberation on the Tobacco Tax Law.

Still, Seares said the Philippine tobacco industry is still waiting for the fat lady to sing.

He even believes local tobacco output won’t fall any further below 43 million kilograms.

“I don’t think it will go below the 43 million kilograms [we produced last year]. We have high demand for global market and they are demanding about 32 million kilograms,” Seares said.

“[Foreign buyers] love our products due to the taste and aroma. For example, our burley cigarette is very competitive against that of American cigarettes,” he added.

The country’s combined unmanufactured and manufactured tobacco exports in 2018 rose by 36.29 percent to a record high of 79.875 million kilograms from 58.606 million kilograms, NTA data showed.

According to the NTA, the increase was driven by the doubled volume of shipments in manufactured tobacco in 2018, which reached 41.963 million kilograms from 18.476 million kilograms in 2017.

The NTA data also showed that the value of the country’s total tobacco exports grew by 60.04 percent to $511.065 million from $319.337 million in 2017.

Seares said the country’s top buyers are Malaysia, Vietnam, Singapore, Indonesia, the United States and Belgium, among others.

You can’t stop

Aside from the bright export demand, Seares believes higher taxes would fail to dampen local demand for cigarettes but only prompt smokers to shift to cheaper brands.

“Once you start smoking, you cannot stop it,” Seares, a medical doctor by profession, said.

Interestingly, a study by Myrna S. Austria of De La Salle University and Jesson A. Pagaduan of the Asian Development Bank revealed the rise in cigarette prices has resulted in a decrease of smoking intensity, or the amount sticks consumed by a smoker, more than in a decrease in the number of users (smoking prevalence).

“The results show that the increase in excise tax has been effective in reducing cigarette consumption in the country and in making cigarette demand more responsive to price increases,” the authors said.

“Specifically, the tax reform has reduced the number of cigarettes purchased by smokers more than the number of cigarette users,” Austria and Pagaduan added.

The study noted its findings are consistent with previous studies that a “rise in income increases the demand for cigarettes.”

“College graduates are more likely to consume fewer cigarettes; poor households are relatively more responsive to increases in cigarette prices than rich households,” added the study titled “Are Filipino Smokers More Sensitive to Cigarette Prices Due to the Sin Tax Reform Law?: A Difference-in-Difference Analysis.”

Floor prices

Seares is urging tobacco farmers to push for higher floor prices during the tripartite meeting in September. Doing so, he explained, would help them cope with the rising production costs.

He pointed out that the floor prices make the tobacco industry unique and more profitable than other commodities.

“Tobacco is the only commodity with floor prices,” Seares said. “Other commodities have no ensured market resulting in unstable prices.”

The NTA conducts a tripartite conference every two years when new tobacco prices are decided upon. The conference serves as a venue for tobacco farmers and tobacco companies (cigarette manufacturers, tobacco dealers and exporters) to evaluate and negotiate the floor prices of unprocessed tobacco leaves.

Vicente believes that farmers would ask for an increase in floor prices, which is more than what they proposed two years ago.

During the last tripartite negotiations in 2017, farmers insisted on a P16.77 hike across all grades to cope with rising production costs.

Vicente added the rising needs of farmers are behind this push for higher floor prices.

Issues in grades

Calindas also pointed to tobacco buyers as also the reasons farmers are seeing their income decrease.

He said some tobacco buyers are downgrading the quality assessment on their produce. Because of this, Calindas said they are forced to sell their tobacco to “cowboys,” their pejorative term for illegal middle-men, during trading seasons.

He recalled his experience during the last trading season in March when a buyer offered P64 to his best-grade tobacco.

“When a ‘cowboy’ asked me, I told him P77 but we agreed on P75,” Calindas said. He sold his product at that price only to learn later the “cowboy” sold his goods to the buyer he originally approached.

Seares said they have conducted training with traders to harmonize standards and leaf grading. Plus, he added, NTA officials accompany farmers to the trading market when dealing with legitimate traders.

He also encouraged tobacco farmers to complain directly to him if they experience irregularities in leaf grading from legitimate traders.

Vicente said that since the floor prices were increased, unscrupulous buyers tend to downgrade the quality of tobacco sold to them by farmers to avoid paying higher prices.

It’s a perennial problem in the industry, according to Vicente, who added this has forced farmers like Capilas to sell their produce to “cowboys.”

“Sa ibang bansa po ang grader ay galing sa gobyerno upang hindi maging biased. Dapat gobyerno po talaga upang wastong mapatupad ang floor prices [In other countries, the grader is a government representative to avoid biases. It should really be government so that the floor prices could be properly applied],” he said.

Vicente said they have been proposing that instead of private entities only NTA officials or employees grade tobacco produce during trading season to avoid certain biases.

Revenue deprivation

Tobacco industry stakeholders, particularly end-users, have been urging the government to curb the proliferation of illicit cigarette trade in the country.

Stakeholders have also cautioned the government that higher excise taxes on tobacco products would encourage more illicit cigarette trade in the country.

In late June, the tobacco private-sector representatives requested a meeting with the NTA board to discuss illicit cigarette trade.

During the meeting, the private sector disclosed that the amount of seized illicit cigarettes in 2018 doubled to 157 million sticks worth P628 million from 89 million, valued at P356 million, in 2017, according to NTA.

Illicit cigarette brands are sold for as low as P20 per pack to P40 per pack in the domestic market, greatly cheaper than the P51 per pack to P78 per pack of legal brands, the NTA added.

Illicit cigarette trade not only damages business operations of legitimate manufacturers but also deprives the government of revenues, NTA said.

Sound the alarm

VICENTE sounded the alarm that the expansion of programs that could be funded by LGUs through tobacco excise taxes could lessen pro-farmer projects even while the industry is still thriving.

He said they have called the attention of LGUs funding projects like construction of water fountains and covered courts, saying these do not benefit tobacco farmers.

“Ang alam nila tanga kami para magreklamo. Pero sa pangalan namin pinapadaan iyong bilyon-bilyong pondo na hindi naman kami ang nabubusog [They regard us as idiots for complaining but they use billions of funds using the name of the organization],” he said.

Rights Services Inc. (Rights) said it is high time that LGUs included tobacco farmers in their budget process.

Rights noted that doing so would ensure that the “sin” taxes allocated to every tobacco-producing LGU would be used for the benefit of the farmers.

“Allowing tobacco farmers to directly participate in the local budget process is expected to further improve their income and eventually help them shift to healthier and more productive crops,” Rights Program Manager Cynthia Esquillo said in a statement.

The last leaf

CALINDAS considers himself lucky compared to other tobacco farmers.

As a Candon City resident, he receives P15,000 (about $286.98) in cash for every hectare that he plants with tobacco. The assistance comes from the excise-tax share that Candon receives annually from Virginia tobacco production. Candon City also provides tobacco farmers with free farm inputs such as seedlings, fertilizers and insecticides, among others.

He explained that some farmers in other tobacco-producing provinces do not receive any assistance from their LGUs.

“Kung gusto pa nila kaming mag-survive, dapat dagdagan pa nila ’yung assistance sa amin; lalo na ’yung cash assistance—siguro P50,000 para sa kahoy, saka konting gas. Pero hindi pa rin iyon sasapat [If government really wants us to survive, they should increase the assistance to about P50,000 for our fuelwood and gas; albeit these wouldn’t be enough],” Calindas said.

Calindas only learned during the interview, a day after the signing of the law, that excise taxes would increase anew next year.

He went temporarily pale, like having seen a ghost, and glanced at the rice farm behind his house.

“Pinirmahan na talaga? Kung ganyan lang din naman, baka tumigil na ako sa pagto-tobacco [The President signed the law? If that’s the case, I may have to stop planting tobacco],” he said.